Jill Trappler paints, weaves, sculpts and makes lace. Woven inextricably into her career is her work in “non-institutionalised” art-making environments. Years ago she and Estelle Jacobs – the former director of the non-profit art gallery, Association for Visual Arts, and board member of several of Trappler’s community projects – organised funding to start an art studio at Valkenberg, the Cape Town state-run psychiatric hospital.

Since then Trappler established the Philani weaving project for mothers and children; Greatmore Street to facilitate studio exchange programmes; and artist exchange workshops called Thupelo, named for a southern African Sotho word that means “to learn and teach by example”.

With the establishment of Thupelo in Cape Town, Trappler was continuing a meaningful tradition established by her uncle, the late South African artist William ‘Bill’ Ainslie, as well as the art-making-and-sharing tradition inculcated in her growing up on her family’s farm.

The Thupelo workshops were started locally in Johannesburg in the mid 1980s by Ainslie and another South African artist, David Koloane – modelled on similar workshops called the Triangle Network in New York, which both artists participated in. Ainslie also established the Johannesburg Art Foundation, which was pivotal for the development of black artists during apartheid when opportunities for them were severely limited. Then, during covid, Trappler set up the Orange Art Project.

She has lived in the City Bowl of Cape Town for 38 years in a house built in approximately 1870 that she describes as “a living sculpture”. She is married to David, a Jungian analyst and psychiatrist, and they have three sons, the youngest of whom works as a film editor for famed South African artist William Kentridge.

My family had a dairy and potatoes farm in the foothills of the Drakensberg. I learned how to spin and knit and weave. My father was an engineer. He sold his business and followed his dream of wanting to farm. But it was too difficult to be a small-time farmer, especially in that area. So, to supplement, my parents had to start doing all sorts of other things. The other part of the story is that they were very anti-government.

My father made the looms and the spinning wheels and we had a ceramics studio and everybody on the farm was part of the various practices. They also started a school. So it was, like, this is what life’s about.

My sister is an educationalist and has the same kind of sense as me that learning is based in making and doing, and conversation and problem solving in that way becomes educational.

She was working for a cluster of foster homes called Home from Home and she said to me one day during the covid lockdown: there’s a mother with eight children and they’re not allowed out of the house; what can we do? So, I said I’ll teach them on the cell phone. It became a kind of a full-time thing as the number of houses grew and then I included other artists.

The artists are contracted by the hour to what has now become a non-profit company. They can teach up to 24 hours a month. They go into the homes and they have become an essential part of the recovery of these children. The children have their foster mum and they have a social worker and they go to school. The so-called mentors, or artists, are their friends and the link to the outside world. So the older children can go off to a local coffee shop with them or to the local park.

I went to boarding school quite soon so I made the most of my holidays learning skills, and all I wanted to do when I left school was to go to Johannesburg to work with Bill at the Johannesburg Art Foundation. My uncle, Bill Ainslie, established it. And Bill was very embedded in the ANC so the school was completely available to everybody.

The school was established to be inclusive: all ages, all colours. Art making and sharing skills, and the ideas that come through art making, makes for a better society. David Koloane and Sam Nhlengethwa came to the Johannesburg Art Foundation.

We started the Thupelo workshops which were also completely mixed and illegal. I mean, in the 70s, all this was completely illegal. And then the Bag Factory opened; it’s a collective studio in Johannesburg.

I don’t see it as charitable or outreach, or whatever; it’s just interwoven into my life: the community work and the studio practice. The individual and the collective are all interwoven.

Everywhere I’ve worked it’s been about transforming people’s lives, or communities’ lives, just in a very small way. And now I see it in the homes. One of the children was six or seven and she wasn’t speaking. By the time she was eight, she was speaking and writing and it was definitely linked into the fact that there was an artist in her home creating a safe space where she could just use her hands and use colour. The artists are not trained as therapists, and leading the project I made that very clear: that they’re not there to heal or interpret. We’re all there just to make things together and to listen. And there are absolutely no assumptions.

Recently I’ve discovered that some of the mothers don’t join in because they feel inadequate. Our assumption is that an adult woman would know how to cut with scissors – you know, cut out of a magazine and stick. That’s an assumption. So it’s about watching and listening and responding; it’s responding to a need.

The children have to leave the foster homes where they’re 18; they’re no more wards of the state. So they go into transition homes and these artists can help them prepare portfolios and also how to stretch a canvas – bits and pieces. I say bits and pieces but it’s a skill that you can get out of bed in the morning and do it rather than nothing.

We use a lot of found objects to make things. Again, because of budget restraints but I actually feel the creativity is enhanced by having to find your materials, having to make a plan. Why should we pick up the plastic off the beaches? Because it hurts the fish. And then you say, but what else lives in the sea, and one thing always leads to another and so suddenly you’re learning geography and biology, but in a completely informal way. It’s imaginative play; it’s being safe within the environment.

It’s just a model that is extraordinary: giving confidence. There are very few schools that have art and, if they do, it’s the same as other subjects – they’re not extending the imagination. There’s a lot of rote learning.

The children are all in the care of the state so we can never identify them in any way, but we can show their work and we’ve shown their work twice: at Spin Street gallery and Artscape. We don’t want to sell children’s art so we swop it for a donation.

What Home from Home has had to do is have bank accounts for all the children. The children get 50 percent of the sales and there’s another learning curve, about money: how to spend your money or save your money. So it’s like an upskilling in every way. So many people just take that for granted. We didn’t learn how to open a bank account at school and these children are now excited by that.

It’s just one person at a time but I do think it makes a difference

At the same time we definitely don’t say, okay, well, make a great picture, it might sell. They really are making images that they’re excited about. The image is what’s important. It’s extraordinarily exciting to see. The images are so full of life. There’s a sense of being part of the world, part of what’s going on around them.

It’s just lovely to see a person coming alive through telling a story by illustration or by paint. Just the physicality of scribbling is really important and then also making something and tearing it up or erasing it. It’s renewal, finding another way of doing things, which is giving you tools in terms of self-management. Why do I feel so angry about this that I want to tear it all up? So you start talking it through. That kind of interaction, in the simplest sense, is actually quite profound.

In one of the interactions I’ve had, I’ve asked who’s that person in the picture, and the child has said it’s my mother. So I said are you going to give it to your mother, and he said to me she’s dead. And I said so what will you do with it, and he said I’ll hang it above my bed. Those three sentences are just so unbelievably loaded but I’m so pleased I had that exchange.

It’s a simple but incredibly effective project. It’s been great because it’s upskilling artists who usually don’t have an income-producing activity because the art market is not so inclusive at all. There are 12 artists and the artists are usually from the community. It’s a very diverse bunch: some are self-taught, some are academics. There’s a psychologist who uses art in her practice as a teacher at one of the schools. There’s an 84 year-old who’s made and done art and taught art all her life. All these approaches are different.

At the moment our annual budget is R600 000 and we’re working with just over 100 children in 22 homes. Government funding is a problem and we haven’t been able to partner with any business funding, which I would ideally like. It is a social responsibility option for a company to take on, but nobody’s done that yet. We are part of the queue for Public Benefit Organisation status, which would be helpful. I’ve never worked in an organisation that has just been given a whole load of funding. The money comes towards you when it’s working. It’ll come. We’ve just got to keep going.

For the first time ever, Trappler is opening her home studio to the public: ‘Having worked so long in an internal way, I’m now going to be opening the doors and opening my drawers and saying, come and see what I’ve been doing.’

25-27 October, 2024

10am-3pm

8 Albert Road, Tamboerskloof, Cape Town

rsvp to jill@jilltrappler.co.za

From the archive

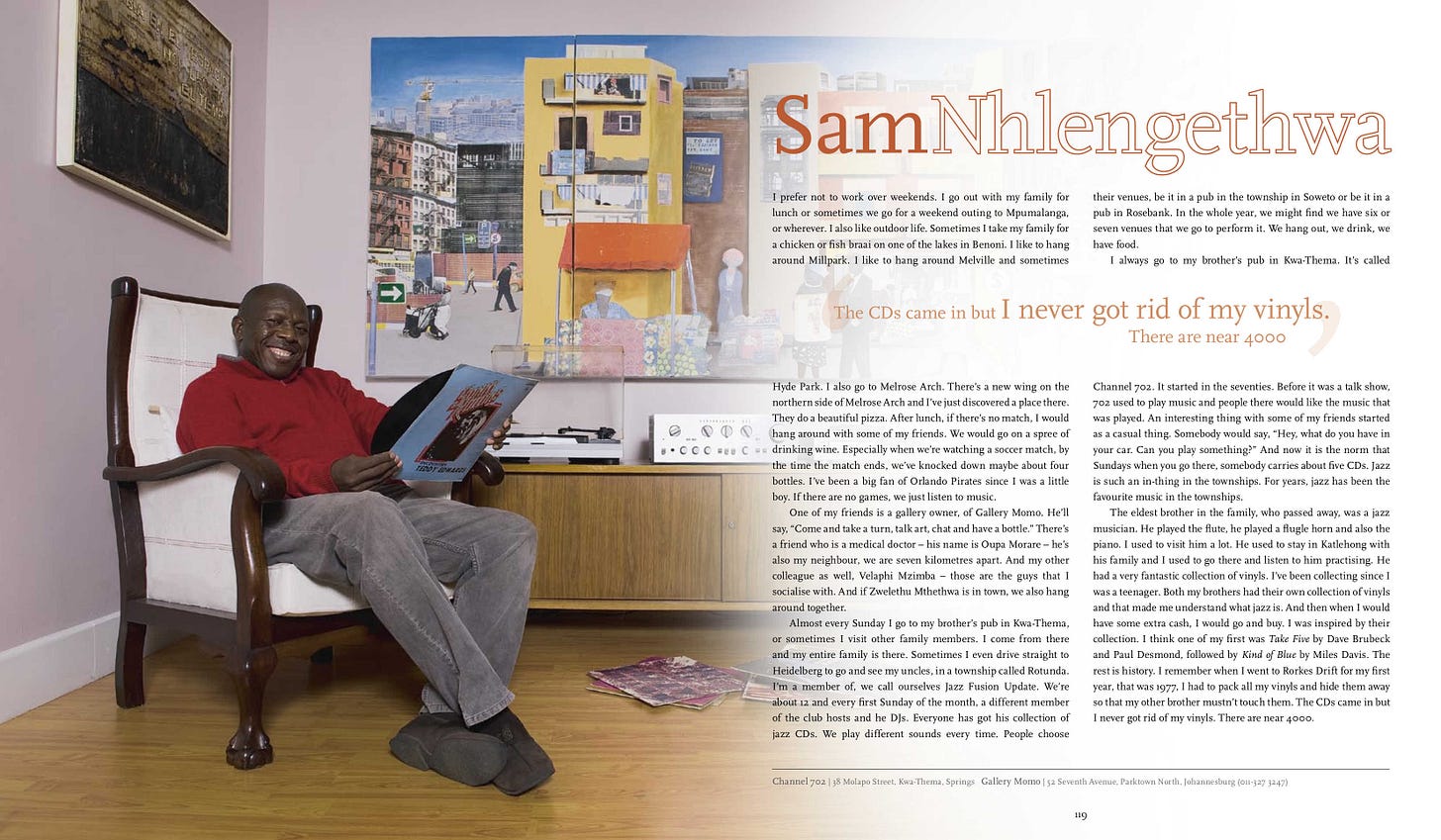

Trappler mentioned beloved South African figurative painter and collage artist, Sam Nhlengethwa, as one of the artists who came to study at the Johannesburg Art Foundation in the 1970s, which was founded by her uncle. Nhlengethwa was later one of the founders of the Bag Factory, a shared artists’ studio space in Newtown, Johannesburg, that Trappler mentioned too.

As a long-time fan of Nhlengethwa’s work and the lucky owner of a couple of his pieces, in 2009 I interviewed him for a book on prominent South Africans and how they spend their downtime. This is the spread from that book, Perfect Weekend (click on the image to enlarge):

Thank you so much for introducing us to South Africans doing creative community-engaging things. This is the kind of content I need to read more of. I love how this immediately plants new seeds of inspiration and a desire to engage with my community too.

Thank you for focusing on this great artist. Jill is a gift to the world.