Show me the one with the spicy sauce

Lunch with Cape Town’s mayor, Geordin Hill-Lewis. A SecretEATS dinner with an Australian chef in a Cape Town skyscraper. And a lesson in making coffee properly from a Danish world barista champ.

“Celery really ruins things”: Lunch with Geordin Hill-Lewis

Cape Town’s new mayor is the city’s youngest ever. In an FT Weekend-style “Lunch with” interview over Cape Malay specialities at the Bo-Kaap Deli, Geordin Hill-Lewis talks about prioritising the city’s challenges, mastering mathematics and where to get the best flat white

I don’t want my first encounter with Geordin Hill-Lewis to be us standing on the street waiting for a table. It is a fairly compact roadside cafe he’s suggested for our lunch. Fortunately, the outside corner table I’ve had my eye on since arriving extra early becomes available shortly before our appointed meeting time of 1.45pm, and I can move from the tiny two-seater on the pavement that’s positioned cheek by jowl with two workmen and a jackhammer.

“This is an awesome place. I love to try new coffee shops because I’m a coffee addict, and I heard about this one towards the middle of last year, I think, and just absolutely fell in love with it because you do really feel like you’re at the heart of Cape Town.” Every eatery in a city should be so lucky to get this sort of endorsement from its mayor.

He apologises for his informal dress, explaining that his suit is at the office in anticipation of Sona that evening (President Cyril Ramaphosa’s annual State of the Nation address). “No suits necessary for lunch in Cape Town, right?”

It’s an historic event to have Sona at the City Hall and it’s due to the fire that destroyed parts of Parliament in January. No adjustments had to be made to gear the building up for the evening’s proceedings – “just the government’s totally over the top security, of course”. Turns out the timing was fortuitous in that the massive restoration project that’s been undertaken at City Hall finished a couple of weeks ago, so the building, apart from being generally glorious, is in mint condition.

Not five minutes have passed since we’ve sat down and a beggar walks by, stopping to offer us SnapScan on his phone as a way to give him money. “That’s a new one”, I say. “That’s new for me as well. Bloody well done; I’m tempted to support him,” he replies.

It’s difficult not to be impressed by Hill-Lewis. At 35, he’s the youngest ever mayor of Cape Town, having followed that up by becoming, at 24, the youngest ever Member of Parliament in the post-1994 democratic era. His mother is a nurse and his late father was a sculptor. His parents met when his mother was stationed at a hospital in Knysna. Hill-Lewis was born in Plettenberg Bay and he and his mother moved to Cape Town when his parents split up. He’s been here ever since, “so for all intents and purposes, I’m a Capetonian”. Money was tight growing up. His mom, who is still a nurse, worked hard and was tough on him to work hard: the overriding ethos that he shouldn’t “waste her time”.

He grew up in the northern suburb of Edgemead where he went to Edgemead High School and where he still lives, about two kilometres from his childhood home, with his wife, Carla, whom he met at school, and their daughter, Ava, who is five. Carla worked as a kidswear designer for Woolworths for 10 years but cut back to half time when Ava was born, and now works for a boutique business management consultancy on design thinking for companies.

“It’s been a while,” says Fatima, who appears to take our order. “Yes, busy mayoring and all that,” he replies. After ordering a flat white, he asks whether they have koesisters available (the koesister is a traditional Cape Malay pastry – sort of like a little, hole-less donut – flavoured with cinnamon, cardamom, mixed spice and aniseed). They’re still making them, she says. He requests that she keep some aside for us. “You’ve got to have one of those,” he says to me.

He orders an item off the lunch menu, the masala steak on a bun (described on the menu as a “Cape Malay take on a Dagwood”), with the steak and the fried egg done medium. “Show me the one with the spicy sauce which was so good,” he says to Fatima, by way of identification. I am delighted to discover I may still order off the breakfast menu, breakfast all day being one of the finer culinary delights anywhere as far as I’m concerned.

Their take on shakshuka sounds interesting – a spinach and coconut sauce with hints of cumin and coriander – so I go for that promising to order the “Hajji Benni” the next time, their take on Eggs Benedict, after Hill-Lewis assures me it is “fantastic”. As Fatima leaves to place our order, he spots Muneer Davids, the owner, and calls him over.

“Muneer, how you man? Nice to see you. You always have the coolest stuff. I love your new glasses.”

“Maybe I must dress you?” Muneer replies.

“Yes,” Hill-Lewis jousts back. “Perhaps you should.”

Is being the mayor what he thought being the mayor would be like? “The problems are intellectually stimulating – that’s the most important thing for me, is that, it’s just interesting. And it’s meaningful; it gives me a very strong sense of purpose. My wife and I are old souls so we love to do jigsaw puzzles and I use the analogy to my wife: it’s like throwing a 2000-piece puzzle on the table and that gives you a huge amount of satisfaction as you put each piece into its place.”

The puzzle pieces appear numerous to anyone who lives in Cape Town, and Hill-Lewis doesn’t disabuse that notion with his laundry list of issues the city is grappling with: a rapidly urbanising city; a burgeoning population in a developing world context so a lot of poverty that comes with thousands of problems – “thousands”, he repeats. Then there are the social problems, namely crime, gangsterism and drug abuse that are also “really massive”.

“And then you’ve got to figure out the real basics which are absolutely essential if you care about people’s quality of life, like sewage and the quality of our roads and keeping the lights on. And all of those challenges – that makes the job fascinating.”

With a tiny tax base cross-subsidising an enormous number of very poor people, there are simply never sufficient resources to cover one’s bases, he explains. “And, by the way, I don’t want to play the victim because we are actually very blessed in Cape Town that we do have a growing tax base – other cities have got collapsing tax bases – so we have a lot to be thankful for, but the service delivery pressures are endless.”

“I always say that Cape Town has a little portion that is basically exactly the same as Munich or Toronto, Auckland. You know, absolutely advanced – even more advanced than some of those places. And then there’s a huge part of it that’s Mumbai.”

With that sort of to-do list, prioritising is itself a puzzle, one might imagine. “You cannot be arrogant enough or naive enough to think that you can fix everything. You have to just pick a few big things. So that’s what I have to do. I want to grow the economy faster by focusing on ease of doing business and load shedding, because every problem in society gets easier with a faster growing economy.”

Fatima intervenes to give us a koesister update. “I’m glad you’re going to taste it fresh because they are, I think, one of the best”, he says to me.

The length of time it takes to get planning approval is the biggest obstacle for businesses to operate easily. That and load shedding. “All the things that we hear about poverty and unemployment in South Africa are basically meaningless so long as you can’t provide enough electricity for the economy to even function.” Then there’s safety and basic services. “So if I can just focus on those three things and move the needle on those three things, then I will have made a positive difference.”

The idea behind the “audacious” decision to enter the mayoral race came to Hill-Lewis just after the first hard lockdown, during what he describes as a “wonderful existential moment”. When the ban on going to restaurants was lifted, he suggested to Carla that they go to a wine farm. With the start of the Durbanville wine valley on their doorstep, ten minutes later they were seated at a table on the verandah of their favourite estate, De Grendel, glass of wine in hand.

“I almost had this emotional moment where I thought, my goodness, we are unbelievably privileged to live here. Where else could you do this? You’d have to live in an outrageously expensive part of California or France.”

While he, too, professes to have a real sense of worry and concern about the way the country is going, he added that he is absolutely committed to making South Africa work and that moment, sitting on the verandah, re-inspired him “that this place is worth protecting and fighting for”.

“And I thought, if we are going to show what is possible in South Africa, that South Africa’s decline doesn’t have to feel irreversible, that you can make progress, that you can achieve some positive and exciting and optimistic things, the place to do it is in Cape Town because it’s got all the right ingredients.”

Those right ingredients – a globally desirable destination; fantastic universities; a rock-solid, healthy and actually growing tax base; lots of expertise; state infrastructure that isn’t collapsed already – makes it vital for the City administration to be a lot more assertive about the kinds of things it’s prepared to try, he says.

He realised his decision was going to be seen as a comment on the incumbent, Dan Plato, “which I didn’t intend at all. It’s just that I had this very strong conviction about what I thought we needed to do in Cape Town, and I wanted to give it a go.”

A lot of the job is reading documents, talking to experts and poring over detail, he says, stressing that one can’t be effective in the role unless one really gets stuck into the detail. What was very new for him was the sheer volume of incoming traffic: the phone calls, the emails, the requests for an audience.

“The most important thing in government is the budget. It doesn’t exist if it isn’t in the budget. That was familiar to me because that was my portfolio (as shadow minister of finance in Parliament for the main opposition party, the Democratic Alliance). The budgeting process is, I think, probably my strong suit.”

During his undergraduate studies at the University of Cape Town (UCT), he enrolled in a PPE degree (philosophy, politics and economics), planning to follow that up with a master’s in economics there. But he had to switch to PPE honours when he flunked the econometrics course necessary to enrol in the master’s at UCT, a course he describes as the extremely statistical side of economics. In high school he achieved six A’s, so this was an altogether novel experience for him (the one subject he didn’t get an A in was maths; he got a B).

“I had never failed anything in life, never – the idea of failing an exam to me was unthinkable”. Having gone through the econometrics course thinking “hell, this is hard”, he still backed himself to pass. “But when I sat down at that exam, I knew, I’m dead.”

At this moment, a man in a MINI Cooper with surfboards stacked on the roof drives by shouting “Geordie!”

“Friend of yours?”

“Yes, that’s Nic.”

Having remained annoyed at being “bested by maths”, Hill-Lewis discovered that a colleague of his was going back to university mid-career to do a postgraduate degree in maths. He asked him why he was doing this. The colleague said he hadn’t done maths at school and he’d always beaten himself up that he had allowed himself to be intimidated by maths.

Finding this story sufficiently resonating, Hill-Lewis registered for a master’s in economics via correspondence with the University of London. “And then I did all the maths and that was the whole point of it. It wasn’t about getting the master’s.”

During that time he and Carla had Ava, so he disciplined himself to get up at 5am every morning to study which coincided with Ava’s wake-up time, “so there I was at the dining room table bouncing Ava on the knee doing maths”.

Despite being an obsessive reader of prominent South African writers and activists – Alan Paton, Helen Suzman and Rian Malan among them – and being raised in a “socially aware house”, he developed an interest in politics only in his second last year of high school, finding the fight brewing at the time between Tony Leon and Thabo Mbeki over Aids and Zimbabwe and the re-racialisation of South African politics electrifying.

He joined the DA in his last year of high school and when he arrived at university, he formed a DA branch on campus. Former DA chief strategist Ryan Coetzee had run a chapter when he was at UCT, but when he left the branch fell into dormancy for more than a decade.

“When I went there I was surprised there was nothing and I thought, there can’t be no branch at UCT, which is supposed to be a home of liberal intellectualism in South Africa. So I started one.”

He had to get 25 people to sign up and pay fees, which he thought would be a cinch. He put up signs on the overhead projectors in all the big lecture halls. The first year politics lecture alone had 600-700 students, and he figured half of them would sign up. “They all burst out laughing. The DA was very uncool.”

By the time he left UCT, the branch had amassed about 250 members. “The key thing for me was not so much the number of members but actually that we sustained the branch; it grew a life of its own. In student politics, your people leave all the time, they’re graduating, so it’s very difficult to sustain the activity.”

Hill-Lewis’ connection to the DA formalised after graduating. He became a staffer of the party, first as an economics researcher, then he worked for Helen Zille in her office and eventually became her chief of staff. Then he ran for Parliament. I assume he chatted to Zille about running for mayor, considering her celebrated stint as Cape Town mayor from 2006 to 2009?

“She had to stay removed because she has a leadership role within the party and that’s part of the decision making process. But I definitely discussed it with her. I often seek her advice on political judgement calls.”

His workdays are long now. The thing that’s important to him – what he believes makes a good mayor – is preparation and attention to detail. But that’s also the thing that’s the most time consuming because it involves a lot of reading. He’ll frequently arrive home at 9/9.30 at night, and still have a hundred pages to read and annotate before the next day, to prepare for the inevitable deluge of meetings and phone calls and visits.

To ensure he gets time with his daughter, mornings with her are non-negotiable and often involve the sort of breakfast item that could slot right in to the menu at the Bo-Kaap Deli. I don’t have children, but French toast every day seems somewhat overindulgent to me. “Listen, I used to make her fresh flapjacks every single morning. That got a little bit hectic so now we do French toast.”

After he gets her up, they play a bit, talk a bit and then he drops her at school at 7.45am. He’s in the office by 8. “She said to me that the only thing that she wants from me is that I must please make all the roads smooth so that when she uses her scooter, she doesn’t have to wobble so much.” He’ll have to add that to a very long list.

The homeless in Cape Town is a big talking point and major concern for many residents. At a recent dinner party, I was told that it’s not politically correct to say “homeless” anymore. The terms “rough sleeper” or “street neighbour” are the more acceptable descriptions to use. Hill-Lewis assures me that it’s still fine to say homeless. “I haven’t heard that,” he says, smiling, referring to street neighbour.

A lot of people, me included prior to this lunch, are under the misconception that once the state of disaster is lifted by national government, the City of Cape Town will be able physically to remove the colonies of homeless settlements that have sprung up all over the show, including all around the oldest building in the country, the Castle, in the central business district. But apparently the City can’t remove them then either.

“Once a structure is permanently or semi-permanently erected and occupied, you can’t just break it down. You’re not allowed to remove them. You have to evict them. And you have to go to court. And when you go to court, you have to provide alternative accommodation as well, at your expense. So really it’s a major problem.”

To help deal with it, he’s just budgeted another R22 million for the Safe Spaces, not quite shelters but places where homeless people can have access to a bed to sleep in, a secure lock-up cupboard, a nurse on duty, showers, toilets and wash basins, and a training programme for drug addiction or job readiness, if the aim is to get them off the street and reintegrated. Cape Town is the only city in South Africa to provide these facilities.

At the moment, the two safe spaces in Culemborg and Bellville can accommodate 350 people in all, but when the 50% Covid-induced maximum capacity restriction is done away with, 700 people will be able to be accommodated again, and the additional R22m will take that total capacity to 1400.

“Then we can go to the court and say we do have an alternative, it’s available, there are clean toilet facilities, there’s healthcare. So that this person cannot actually refuse that offer and we can move them.”

He reckons it’s difficult to name a figure for those who would need to be moved as it’s a number constantly in flux. He quotes one NGO that pegs the number at 14 000, but he doesn’t think that’s true.

“Interestingly and despite everything that you hear in the media about Cape Town and homeless people, the very first lady I spoke to was a lady called Carol all the way from Mpumalanga, who’s only been in Cape Town for six months. And she said to me – straight off the bat, no prompting – Oh, I came to Cape Town because on the streets in Johannesburg there was nowhere to sleep, no-one looks after you, everyone beats you up and steals your stuff and everyone knows that Cape Town is where you get the very best care and you look after people like us.”

That’s a real double-edged sword, I comment. “Yes, it is a double-edged sword but the thing is if you believe the media narrative, we’re like these evil vampires. I challenge any journalist, anytime someone says to me: Oh, you don’t care for homeless people, I say, have you been to a Safe Space? If not, don’t talk to me.”

They will need to build more of them, he acknowledges, with plans for one in the southern part of the city, in the Muizenberg area. One wonders though: you build them and then more people arrive to live on the street. It seems an insurmountable problem; how do you ever get on top of it? “It’s really difficult. It’s one problem that is really hard to know what to do about,” he replies.

The one hopeful bit of news is that the City seems up to the task; Hill-Lewis says he has “a lovely team”.

“That’s one of those things that I think sets Cape Town apart: a civil service that is professional, experienced, world class.”

And then he launches into a discourse that wouldn’t be out of place accompanied by the swell of a Hollywood blockbuster score: “At the moment I’m talking a lot about civic pride. This is a collective home and I talk to the staff a lot about this, about showing pride in your work and what that means because there are so few examples of pride in government in South Africa. We’ve come to accept the mediocre, the totally mediocre, the lower than mediocre. We’ve come to accept failure. And so if we expect citizens to help us keep the streets clean, to report criminal activity, to not steal copper cables, among other things, we must demonstrate pride as well by doing basic things like answering our emails and making sure that you get back to people who are looking for you or that you go the extra mile for someone who needs help.

“There’s a whole lot of things in small, seemingly imperceptible ways that we can show that this place is different and better and strives for something better. So I know that’s quite esoteric but that’s important to me, this concept of civic pride, that we don’t allow ourselves to accept the standards set by the rest of the country because we have to unashamedly aim for something better than that.”

Hill-Lewis doesn’t rule out leaving politics in due course – “there’s an entire universe out there of fascinating things that I’d love to get involved in” – but equally he could see himself sticking with it. The opportunity to work in national government would certainly be attractive.

At this point Fatima makes her less-than-triumphant return. Turns out someone found the hiding spot where she was keeping the koesisters, so the kitchen is now making fresh ones for us. Considering I’ve long overshot my allotted time with him, I suggest we get them each to go.

Before they’re brought out, we switch to my favourite subject: where does he like to eat out? “I mainly do coffee shops. I don’t often eat out. My absolute favourite is Deluxe at the top of Buitenkant Street. I always order a flat white. I once tried to get rid of the milk and have an Americano, but I just can’t. I just can’t,” he repeats.

He’s also keen on the Courage mobile coffee bar and is very loyal to his neighbourhood local, Bean Authentic. He and Carla are newly into ramen and poke bowls and Three Wise Monkeys in Sea Point is where they like to get them. Their steak restaurant of choice is Fat Butcher in Stellenbosch, Willoughby at the Waterfront for tuna steaks, and Vintage India and Moksh for curries.

“Actually, next time I’ve been meaning to try that curry,” he says, gesturing across the road. “I’ve never been to Ahmed’s Tikka House. Look how cool it looks, hey? We have to go try that.”

He also likes Foxcroft in Constantia and Chefs Warehouse in town and for a pushing-the-boat-out meal, La Colombe for its winter special full tasting menu when the price comes down from about R2000 a head to R695 – one of the city’s best kept culinary secrets, as far as he’s concerned. “We make a habit of once a year, in the middle of winter, of going to La Colombe. We’ve actually never been in the summer for exactly this reason.”

At home Carla usually cooks dinner: simple, hearty fare such as lemon chicken pasta and tomato bredie. Hill-Lewis doesn’t eat pork and doesn’t like the taste of green peppers or celery. “It’s the same as green pepper for me, celery really ruins things. Other than that, I’ll try anything really.”

And, right on cue, our long-anticipated koesisters arrive. “We have to do one of these together,” he says, as we open our respective takeaway boxes and bite into them. And then he’s off, hopping into the backseat of his CA 1 number-plated car.

Speaking to Hill-Lewis for a couple of hours makes me think of that line from the movie Four Weddings and a Funeral when Hugh Grant’s character says, “I don’t know what the fuck I’ve been doing with my time”. And then it dawns on me. In Cape Town, Hill-Lewis never has to search for a parking space.

Bo-Kaap Deli

114 Church Street, Cape Town; 064 518 4231

Watermelon juice R40

Flat white R25

Green Goddess shakshuka R110

Masala steak burger R135

Koesisters (2 x portion of 3) R40

Americano R20

Total with tip: R415

scene@ a SecretEATS dinner

Friday, 11 February, 2022

If entering the confines of Hotel Sky in Cape Town necessitated sunglasses, one also needed a microscope to examine the portions on offer from 2017 MasterChef Australia contestant, Ben Ungermann, and his take on Indonesian fine dining, at the latest in a series of SecretEATS events.

With no surface or seat not rendered reflective, shiny, technicoloured or upholstered in vinyl animal print, it’s a mystery why the developers of this assault on one’s senses thought any distraction whatsoever was required for a building with 28 storeys and the sort of unobstructed panoramic urban vistas most city hotels would kill for. Attention could perhaps have been better diverted to the ponderously slow elevators, only half of which worked that afternoon until they too gave up the ghost the next morning.

“I’m more hungry than an hour ago. I’m currently in a state of disaster,” said the German, who has what one might euphemistically describe as a healthy appetite. This declaration came after the second course, which featured a garnish-sized serving of fried rice. It followed an assemblage of minutely-balled scoops of fruit in a spicy sauce. What the fruit salad lacked in volume, though, it did make up for in visual pop, as Ungermann did the rounds fogging each bowl in dry ice.

“The first question is, will it be bigger than a square centimetre?” the German continued, in anticipation of course three, the final one before dessert. Once placed on the table, he gazed down ruefully. “I’m looking forward to breakfast, I must say.”

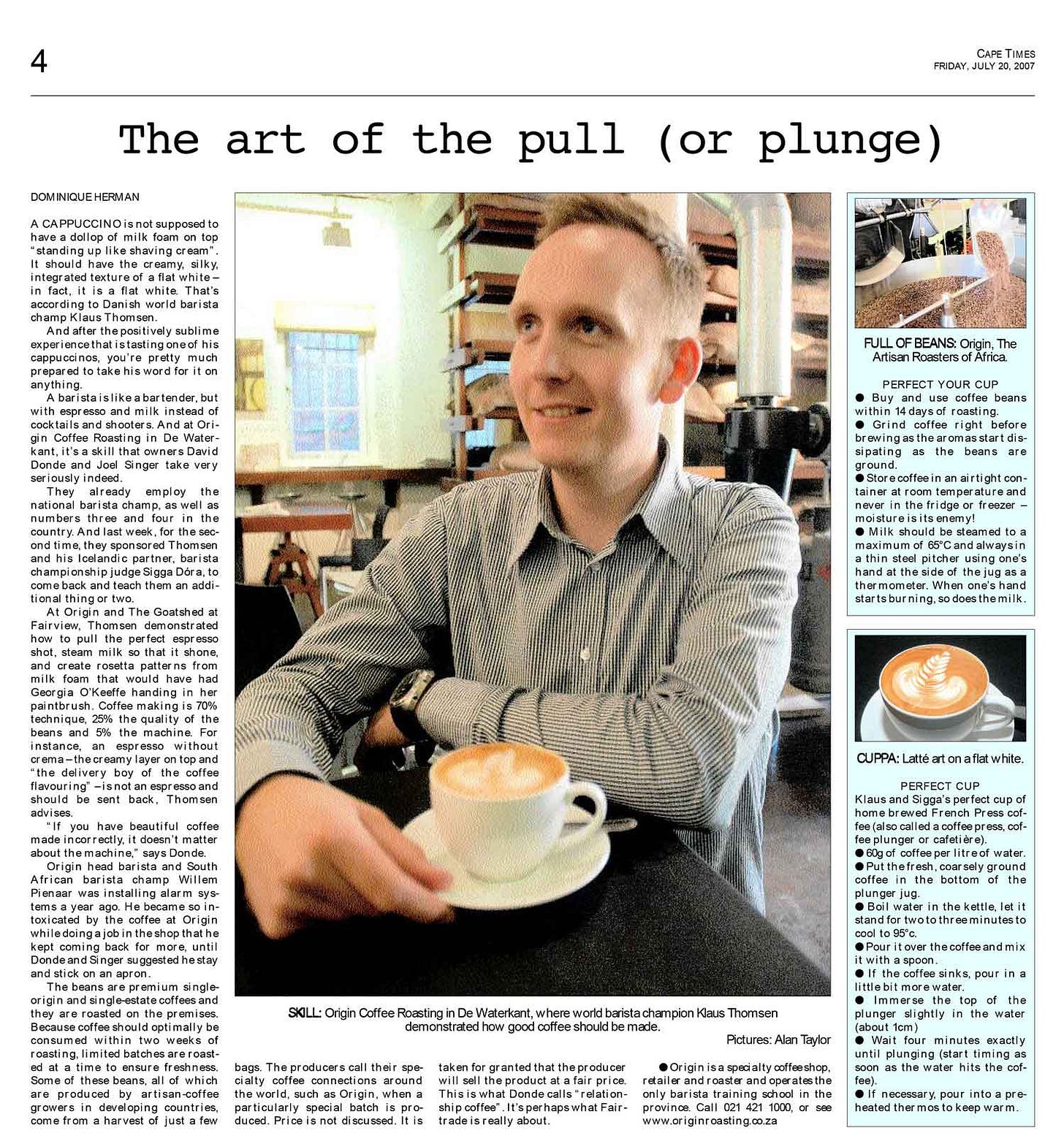

A flat white from the archive

About a 10-minute walk from the Bo-Kaap Deli is Origin, which is, I believe, the original roastery-on-site coffee shop in Cape Town and certainly the one that spun a web of boutique roasters across the city, including the ones Geordin Hill-Lewis mentioned. When I was a staff writer at the Cape Times, a fun break from news reporting would be to cover an event such as the coffee masterclass of then world barista champ, Klaus Thomsen, which I did in 2007, a year after Origin opened. Origin is still doing its thing in its original location, but co-founder David Donde left a while ago to set up Truth Coffee. His steampunk-themed cafe was declared one of the world’s best coffee shops by the UK’s Telegraph newspaper. Whatever your feelings on those best-of lists, there’s no disputing that having a cuppa there is an experience worth having, perhaps after you’ve done the rounds of Hill-Lewis’ favourites.