'I want to get to the top of the mountain'

Over pita wraps and fries, sports physiotherapist Helen Millson recounts an action-packed career punctuated by political milestones, controversy and lots of firsts

Helen Millson is not winning on the drinks front. Since there was “plenty of wine” at a friend’s 60th birthday party the day before, she’s not keen on having any at lunch – “I’m not a big drinker” – but her first and second choice soft drinks, Dry Lemon (“very boring”) and freshly squeezed orange juice, are both unavailable. So she settles on tap water with ice and lemon.

We’re sitting outside at the restaurant at the Cape Town Hellenic community centre in Mouille Point (run by another Helen) with sports fields and the Cape Town Stadium looming large in the background. The stadium is now home to provincial rugby – a move that caused much consternation among those who felt its traditional, 130 year-old base in Newlands was sacred.

Millson is one of them: “I’m not only anti; I’m a thousand percent anti,” she says. “If you want more non-white people to play, move it to the townships.” She’s been to one rugby match and one soccer match there. The rugby match was between the Stormers and the Bulls, two South African teams based in Cape Town and Pretoria respectively that compete internationally. She sat with former colleague Gert Smal, who recruited Millson to be the physio for Western Province (WP) rugby in 2000 and, at the end of her first year, asked her to be the team physio for the Stormers too.

At the stadium, Millson was supporting the Stormers while Smal was at that stage the Bulls coach. “I said, ‘Gert, I thought we were friends but I’m not so sure now’. Just after that I went to watch a soccer match and the soccer was fantastic but I just looked around at all these people who’ve had to be commuted in. How can they afford to come and watch?”

Millson orders the lamb wrap in pita bread. “That’s a very popular one here,” responds Beverly, our waitress. “Do you want tomato, onion, everything inside?”

“The whole bang shoot,” Millson replies.

We can’t order sweet potato chips due to the country’s rolling power outages which have coincided with lunchtime in this area, so we go for a plate of regular chips to share instead. “I hardly ever have chips,” Millson says. Much as I’d like, I can’t say the same.

Sport and politics have always been inextricably linked for Millson. She’s had the sort of exposure that physiotherapy students in university now can only dream of, but because a lot of it took place before the era of professional sport in South Africa, when the country was an international pariah state due to apartheid, a lot of her labour went unpaid.

“My career’s been phenomenal and it goes parallel with the politics in sport and the politics in South Africa. No one’s had the experience that I’ve had,” she says. Her CV runs long and includes multiple provincial and national sports: cricket, rugby, hockey, tennis, squash, bowls, golf, soccer, volleyball, swimming, diving, surf lifesaving. Her private clients are all athletes, including marathon runners, cyclists, gymnasts, powerlifters and martial arts practitioners.

She’s been the official South African physiotherapist at the Commonwealth Games, All-Africa Games, the Windsurfing World Championships, the Maccabi Games, the World Adaptive Surfing Championships. “No other physio has had that. Nowadays physios mainly do a specific sport such as cricket or rugby: they specialise. I’m lucky to have done that whole bang shoot.”

After Nelson Mandela was released from prison in 1990, South Africa was invited to the Lifesaving World Championships in 1992 in Japan. It was the first time SA had ever competed in surf lifesaving world champs. It was a transition period in the country’s history and at that stage there was no flag or anthem yet for the new democratic dispensation, so the team sang We are the Champions instead. Millson was officially the “chaperone” although her role was physio. Because the team consisted of four men and two women instead of the mandatory equal number of men and women, she was also recruited to participate.

“At the time I wasn’t a young chick, but I was very sporty so I took part in five events.” She had been kayaking once in her life, in a double canoe, so she took part in that and came third last. In the 2km run on the beach she didn’t come last, but in the other events she did. Even so, she managed to accrue points for each event. “You’re doing it for your country.”

The Commonwealth Games in 1994 in Canada was the first time in 36 years that South Africa was permitted to enter. The Queen was in attendance, Prince Andrew hosted the team at a reception, South African singing legend Miriam Makeba performed. South Africa was new to democracy and the racial dynamics in the team weren’t without friction, but once the brand new South African anthem played and the new flag was held aloft, they all held hands and cried. “We were so moved,” she says.

Two years before that, Millson was thrust into the domestic spotlight. She was chosen to be the physio for a newly formed national rugby team that could participate internationally. This was yet another unpaid post. Millson was living in Port Elizabeth at the time where she ran a private practice and contributed her time and skills on the side to Eastern Province (EP) cricket and rugby.

The psyche of a sportsperson is often “mal in die kop”, she says. ‘There’s a madness in the head. It’s what I am; it’s how I relate.’ She also finds sporty patients highly compliant. ‘They want to get back and they’ll do what is required’.

“Danie Craven was the icon god of SA rugby. And he said in the press that ‘in a hundred years, there had never been a woman involved in rugby. I do not want a woman involved’. It went viral and they had pictures of me all over the Afrikaans press – caricatures of me going into the change room: big boobs, tiny little waist with a physio bag.”

Headlines such as Would you let a woman touch your groin? And Dok Craven en die blonde ‘probleem’ were plastered across newspapers and Millson received calls from international broadcasters, all of whom she refused interviews. “My kids were going to school and their mother is on the front page with that kind of smutty stuff.”

She contacted Dr Ismail Jakoet (who was the chief medical officer for the Rugby World Cup in 1995 which SA hosted and won, and where Mandela famously wore the Springbok jersey when he presented the trophy to the then captain Francois Pienaar, a white Afrikaner) and said, “Look, I’m resigning. I don’t need all this. I can’t travel with them anyway because I’ve got three little children, so get somebody else. He said, and it was another life lesson: ‘Helen, did you do anything wrong?’ So I said no, and he said, never resign if you’ve done nothing wrong.”

So Millson wound up being the first physiotherapist for the South African national rugby team post-apartheid. “Danie Craven was trying to get rid of me. To this day people think I was kicked out but he couldn’t kick me out,” she says.

Adversity wasn’t a new experience for her. Millson’s father died when she was 11 and her mother struggled. “She had no money. My sister and I virtually brought ourselves up.” They moved from Johannesburg to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and lived in a “tiny flat” in Bulawayo. Millson’s parents were both from German Jewish families; her father’s family from Cologne, her mother’s from Berlin. The families moved to SA when her father was 19 and her mother 11, meeting later in Johannesburg. “They arrived in South Africa with nothing. The kids couldn’t speak English,” says Millson of her mother and aunt.

In Rhodesia, another German Jewish family who owned a tie factory “adopted” them and gave Millson’s mother a job selling ties. She travelled around driving on strip roads with suitcases filled with ties. “I’m a Zimbabwean, absolutely. I loved the people very much, black and white. I loved the lack of materialism, I loved the bush, I loved the wildness – everything about it. I could live there tomorrow,” she says. Millson’s daughter has recently adopted a Zimbabwean baby.

Millson’s older sister wanted to study physiotherapy. There was no place to do that in Rhodesia and their mother didn’t want to send her to South Africa “because of apartheid, which was phenomenal because my mom had no money, so it was a huge sacrifice”. So their mother scraped together a loan to send Millson’s sister to study in Bristol in the United Kingdom. Having skipped a year of high school and completed her O Level age 15, when it was her turn Millson was keen to study psychology and sociology (and she received a scholarship from the University of Cape Town to do this).

But she was talked out of that after the headmistress of Millson’s school called her mother in. “She said, Helen shouldn’t do sociology and psychology because it’s a rich man’s daughter’s profession. There are no jobs for her and she should rather do physio like her sister.”

So Millson also enrolled in Bristol at age 17 in the late 1960s. She didn’t see her mother for three years, there being no money for her to visit. “I absolutely hated physio. I didn’t like anything about it. It was so boring. The teachers there were so old-fashioned. I was often in trouble,” she says.

At lunchtime Millson would swim in the pool, which wasn’t allowed, and then she’d go to afternoon lectures with her long hair tied up wet, which also wasn’t allowed. The faculty called students in when they qualified to give them a character assessment, and they said to her: “We have decided that the reason you are irrepressible is because you come from the wilds of Africa and you’re used to roaming with the lions and the tigers.”

“Now, I was in a tiny little flat bringing myself up, and definitely a most obedient person. I would never sleep around, I never took drugs – it was the drugs time, hippie time. I would never let my mother down, except for hitching around the world (didn’t tell my mother).”

‘I’ve always wanted to save the world even when I was little. I’ve always been, like, “I’m going to save the world”, which I now realise I can’t. I’ve only realised recently,’ she laughs.

After graduating, Millson returned to Rhodesia and went to work in the public Mpilo Hospital in Bulawayo. She also worked with the Rhodesian Bush War wounded at the St Giles medical rehabilitation centre in Harare. “It was so much more meaningful for helping people than psychology or sociology because when you’re hands-on, do you know how much psychology is involved, how much sociology is involved? My mother pushing me into physio was the best thing; I’ve made it work for me in every brilliant way possible.”

Millson was married to a South African civil engineer for 25 years. They lived in Rhodesia, where he worked on projects in the rural areas, with their two sons and daughter, all of whom are in their forties now. Millson was a locum when her kids were small and took bible studies classes so she could tap into her husband’s Christianity for the benefit of their children with regards his family. Her mother-in-law was a Jehovah’s Witness. Millson subsequently embraced her reform Jewish heritage and maintains it.

In the eighties, after Rhodesia achieved independence from British colonial rule and became Zimbabwe, Millson’s husband wanted to leave. “At the time I thought of leaving him because to bring the kids now to South African apartheid was everything I disagreed with, but I couldn't divorce him based on my politics. We had three little children so I had to leave. I was gutted. My whole raison d’être was politically to make a change and now we had great opportunities and he wants to move to South Africa.”

In Port Elizabeth, where they settled, she wanted to minimise her workload to focus on her children but she needed to earn an income. So in 1990 Millson’s mother financially backed her for a basic sports injuries practice setup to operate out of the garage. Five patients a day would cover the costs of her daughter’s university studies at the time.

‘You touch and you feel and you listen. They opened up a lot; they asked me all kinds of things. One guy one day asked me, “Helen, I need your help. My very best friend of the last 10 years broke up with his girlfriend of five years about 18 months ago. Now she and I are absolutely in love. Do you think I can go out with her, but he’s my best friend?”’

The practice became busier and busier. Eastern Province (EP) cricketer Brett Schultz arrived with a bad knee. Millson was familiar with cricket but felt she had to learn more about the sport, so she would go watch live matches on Saturdays and make notes – specifically what was demanded of a bowler. “Even to this day, I won’t treat anybody unless I go and analyse what they’re doing.” She was then asked to be the team physio for EP cricket and, later, EP rugby.

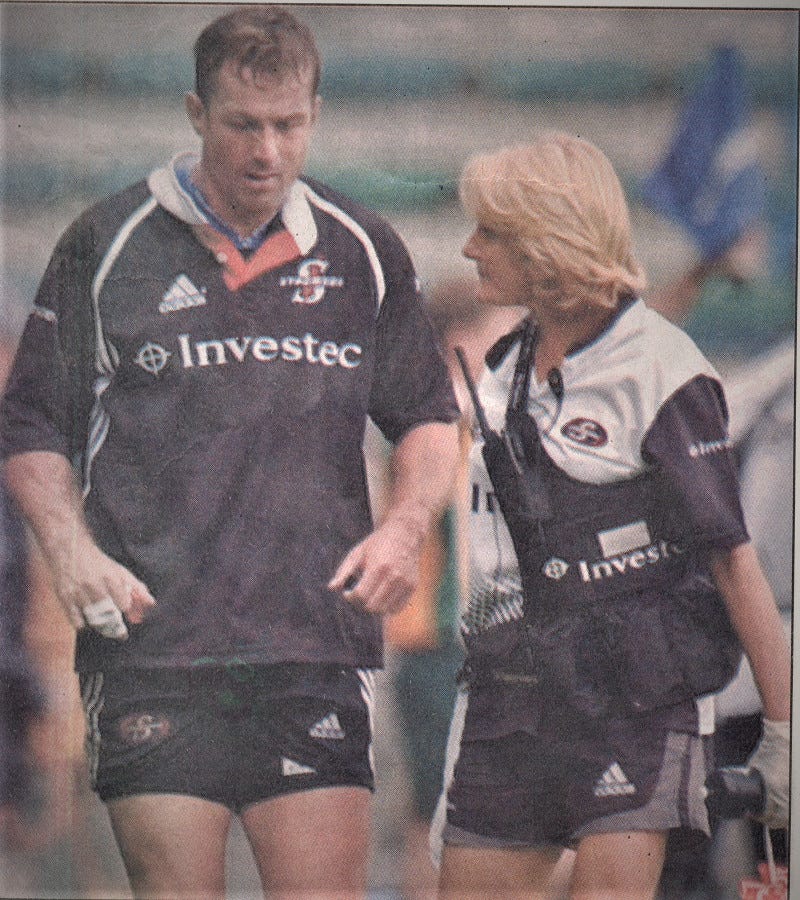

After divorcing her husband, she moved to Cape Town in 2000 where she worked with the provincial cricket and rugby teams there, including her five-year full-time stint with the Stormers. The Sports Science Institute of SA’s head physio had approached her to be a partner in its physiotherapy practice, which she turned down.

“The rugby team was very good for me in terms of politics because I had historically partnered apartheid and Afrikaans, and I was bemused by the fact that the Afrikaans boys were awesome: they were respectful, they were kind, they were gentle – not in the field, but in general. They were the most fabulous people. The management staff were also amazing people. It was the best time of my life. I loved it so much.”

One year when the Stormers performed very well, the players received bonuses. “Not me. I’m working on them every day to get them back. I remember De Wet Barry had a torn hamstring and I worked on him twice a day seven days a week to get him back in time for the semi-finals. The guys were so embarrassed about me not getting a bonus that they all clubbed together and gave me a bonus,” she said.

In 2006 after she left the Stormers, national rugby wanted her back but she felt that wasn’t the right move. “I never go back in life. I’d been there.” Then she was headhunted to be a medical advisor to insurers for Premier League football, England cricket and professional golf in the UK, where she’d be earning a decent salary in pounds. “I couldn’t care about insurance, I couldn’t care about money. That’s been my downfall, but I don’t care. I’ve always had enough money to live.”

Millson wasn’t convinced but her mother wanted her to accept the offer. She was 83 and dying of cancer. “She grabbed my hand and she said, ‘Please, I know you just want to work in the community but I want to die knowing that for once you’re earning money’.”

So Millson went to the UK for 10 years, based in Suffolk, and even though she moved back to Cape Town in 2016, she’s still involved in the work as an independent consultant. “I loved it there but I’ve always been very political. I love Africa, especially Zim, with such a passion and I thought, what am I doing here having the most brilliant life?

“I mean, I went kayaking in Croatia, in Finland, in Sardinia; cycling London to Paris, London to Denmark, London to Holland; hiking in Peru, in the Pyrenees. You just ignore the weather. I started feeling guilty about all those years of fighting for Africa and I thought, what am I doing here?”

‘My greatest strength is knowing what I don’t know’

Apart from Paris Saint-Germain, the most recent addition to her European clientele is German football club Bayer Leverkusen. Prior to a recent trip to meet with the team for the first time in person, she endeavoured to brush up on the German she used when her grandparents spoke it with her. “When I sat down and spoke German, just like that they liked me. It makes such a difference.”

On her return to Cape Town from her England stint, she immediately involved herself with several public hospitals’ sports injury clinics, as well as charitable organisations such as Project Playground, a Swedish initiative in Langa, and she started working with coaches in Khayelitsha on preventing injuries and enhancing performance.

“I’m very wary about being a white woman coming to do good in the townships,” she says. So now she focuses on her pro bono work at Groote Schuur, a public hospital, where she spends every Wednesday morning attending to children with sports injuries. She also travels giving talks she’s developed. They include Excellence in Sport/Life and The Role of a Woman in a Man’s World/Man’s Sports World.

Apart from SA women’s hockey, Millson had never worked with female sports teams before. At the end of last year, she was asked to treat six WP female rugby players. “A lot of stuff has not changed,” she says, unwilling to say anything more on the record.

Her third major talk topic is Hip and Groin Complexities and whether prevention of injuries is indeed viable. It’s a subject that formed the springboard for her professional PhD, which was based on a thousand studies and involvement in multiple academic conferences plus personal experience. This was completed through the University of Kent in England in 2020 (she did a Master’s Degree through UCT in 2003 with well-known sports scientist Tim Noakes and Professor Mike Lambert as her advisors). Prior to her focus on hip and groin, she had put together two handbooks on the latest global research on knee injuries for the Premier League.

“My big thing was prevention where possible so I massaged these huge, big guys all day long. It makes you fit. Everybody wonders why at my old age I’m still hiking, cycling, kayaking and it’s because my whole career was very, very, very fit-making.”

She won’t reveal what the “old age” number is however. She always used to say her age, she says, but being with the Stormers changed that. “I used to run up mountains and jump off cliffs with them and they were going, ‘You’ve got kids our age. Our mothers would be sitting watching us. How old are you?’ And they kept on asking me and I decided I’m never going to tell anybody ever again because they’re putting me in a box. I will not be put in a box. I don’t care if I’m the same age as their mother; I’m not the same as their mother.”

‘Most important are my three children and five grandchildren. No matter what a fabulous career I have had, by far the most important thing for me is my family.’

At school she was games captain, in the provincial gymnastics and hockey teams as well as on the national diving team. Over-35 she played provincial squash and tennis. “But now I’m not interested in any competitive games. I just want to be in nature. I want to get to the top of the mountain. I want to kayak as long as I can. I want to cycle.”

A week before our lunch she went on an eight-day kayaking trip up the Garden Route. She started kayaking because years ago she was asked to be the physio on the 250km open ocean PE2EL Surf Ski Challenge in the Eastern Cape. She’s subsequently joined the team as physio seven times over 14 years. “And there’s no ways I’ll go along and not be able to do it and understand it.”

On a hiking trip in the Pyrenees in the past year, she had trekked to the top of a peak carrying a 17kg backpack. An elderly man and his son were coming down and the son came running over to her. He said his father didn’t speak English and had asked him to ask her how old she was and to tell her that she shouldn’t be hiking up that mountain. “People ask you all the time because you’re doing stuff you shouldn’t be doing.”

The Greek Club Restaurant

Hellenic community centre, Cape Town

Lamb wrap R80

Vegan wrap R70

Chips side R25

500ml sparkling water R20

Cappuccino R25

Americano R20

Total including tip: R270

In an upcoming newsletter, I delve into the surprisingly complex world of apple and pear growing and exporting. Buks Nel, one of the men I chatted to for that story, has one of the more interesting jobs I’ve ever heard of: he patrols orchards on the lookout for new varietals. Anything that looks out of the ordinary to him could result in a new commercial strain of apple or pear.

On March 16 at 6pm, Buks will be reading from his latest book People, Pears and the stories they share at the Somerset West Library with his wife, Ros, who illustrated the book. This is the third in a trio of books about apples and pears that he co-authored with Henk Griessel, whom I also interviewed for the story.

The library is located on the corner of Victoria and Andries Pretorius Streets in Somerset West. Please RSVP to brianb@tru-cape.co.za or notify the library directly on 021 400 4820 or nizam.bray@capetown.gov.za