Ciao Town

Trattorias marked the start of contemporary restaurant culture in Cape Town. Restaurants such as Venezia and San Marco were in the vanguard of creating the city’s dining-out scene.

The food story that has captivated my attention for many years is that of Italian immigrants to South Africa and how their tastes and traditions went a long way to creating the robust restaurant culture in Cape Town today.

I’ve written variations of this story over the years. One is at the very bottom; one is here, another is here and another here. I’d always planned to write a book on the development of the restaurant culture in Cape Town and how the city came to be the eating-out capital of the country. I envisioned an anthology of long-form journalism pieces on each chapter of that development: the notable people, places and products responsible for that trajectory.

Having subsequently started this newsletter, though, I’ve decided rather to publish the stories intermittently here. The first one begins with the first Italian restaurant in Cape Town:

When Gilda del Mistro relocated to South Africa before World War II, she noticed there were no ice cream shops in Cape Town. Her brother-in-law, Aldo Stefanutto, had an ice cream shop in the Italian city of Pescara on the Adriatic Sea. But when Pescara became the target of repeated bombings during the war, Aldo and his wife Onorina took their children and fled to northeast Italy. Aldo then left Italy in 1948 for another peninsula in South Africa, and, in 1951, the rest of the family followed on the Union-Castle Line.

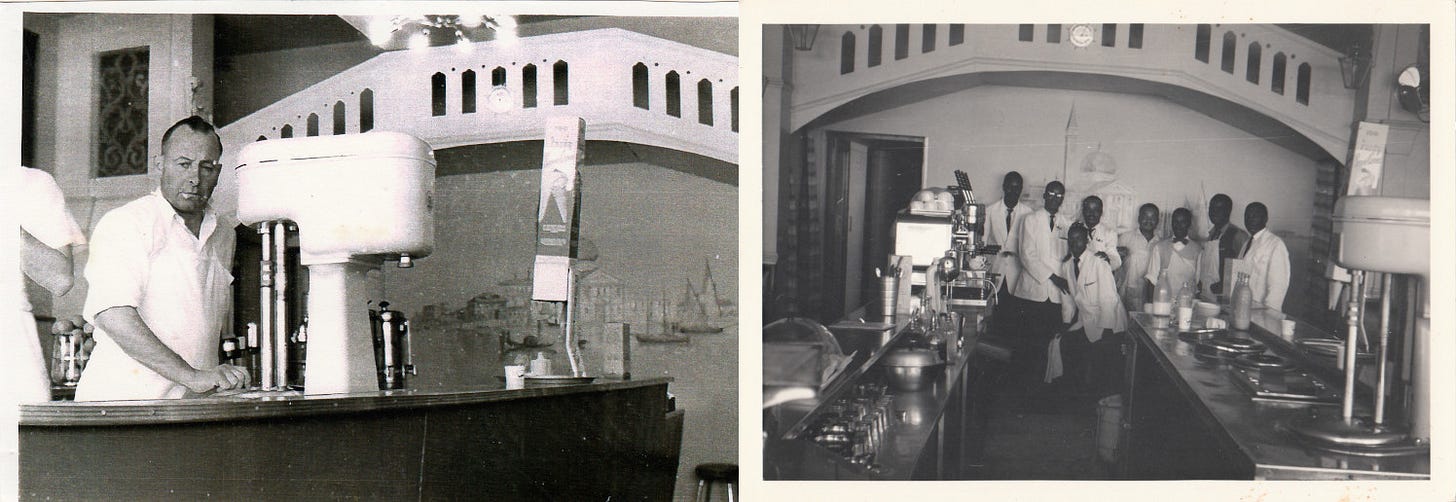

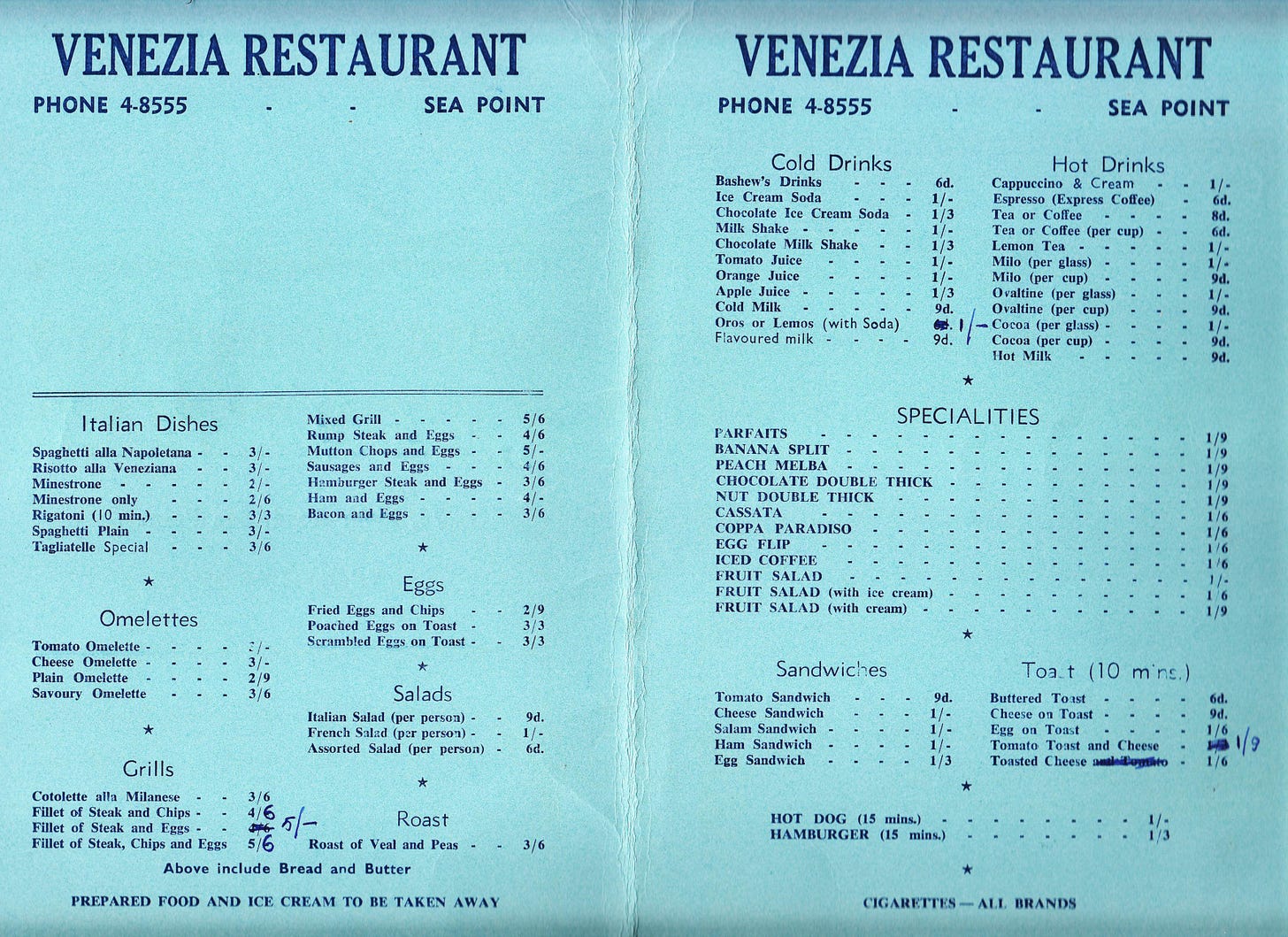

In 1953, after fulfilling a mandatory work immigration requirement in his trade of terrazzo, Aldo opened Venezia on the Main Road in Sea Point, then and now a mixed-use neighbourhood on the Atlantic Seaboard of Cape Town. The restaurant had nine tables and jukeboxes. A life-size gondola protruded from a mural of a Venetian water scene on the back wall. The arcs of the gondola served as coffee and ice cream counters, with seating booths on either side against the walls.

When they took the space, Onorina noticed a kitchen in the back, so she started cooking pasta there. “People did not even know what pasta was in those days,” said Franc Stefanutto, Aldo and Onorina’s younger son. So, Onorina stuck pieces of spaghetti and tagliatelle onto the menu.

“There were no restaurants, no places where people can go like at home. When people went out, it was to a hotel and to a fixed menu,” he said of the Cape Town dining scene at the time. “As far as we were concerned, we were the only restaurant here. That was the only one.”

Carol Stefanutto, Franc’s wife, described Onorina’s cooking as quite simple: “They were really basic recipes, but everything was tasty and nice. I think that’s really what people wanted. It was novel – that’s the point. I know it’s hard to believe but you didn’t get pasta here. A lot of people who came here were of English origin and they made macaroni cheese.

“I remember having Fatti's and Moni's: you had the long macaroni and then they broke it up and they made it into macaroni cheese. Or you had what we call the thin capellini now – angel hair – but it was called vermicelli, and it was also broken up into soup. And that was about the extent of the knowledge of pasta.

“You know, standard South African food was a meat, potatoes and two vegetables. You got curries – that was the other thing – but it’s a completely different flavour from the piquant of the tomato, basil, garlic. So there were the different flavours that come into Italian cooking that then came into South African cooking. It was just a completely different way of cooking.

“Apart from the food, they brought a different concept to eating. Having wine with your meals: this was a completely new phenomenon. Franc’s father brought in the first espresso machine. You didn’t get espresso here. The first time I had a cappuccino was there.”

Her first time at Venezia, though, was long before that. “I must have been about 10 or 11 and an aunt of mine lived in Sea Point and that was my treat, to go and get an ice cream. I do remember on a Sunday, that there was a queue right the way round the block.”

The restaurant took off more quickly than the ice cream did. Making ice cream like he had in Italy proved tricky for Aldo: he couldn’t find peanut butter for the peanut flavour but, more importantly, the milk wasn’t rich enough. He had to put cream back into the milk.

“One thing about my dad: he had a tremendous nose,” Franc said. “If I tell you how many lemons were squeezed to make lemon ice cream, it must have been to the millions. He used to walk past me when I was squeezing and he says, ‘Franc, there’s a lemon here that’s not right. Don’t squeeze it because it will spoil the whole flavour of the other ones.’ He knew exactly where it was. He would find it.”

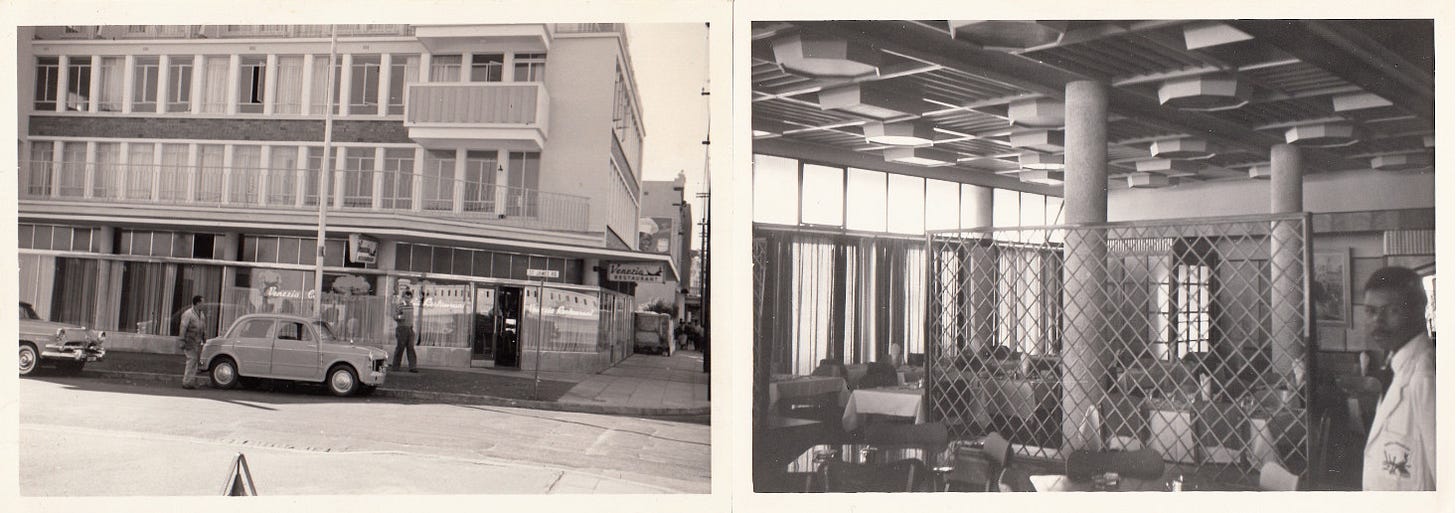

As the restaurant gained in popularity, it got bigger and bigger. First they extended the shop backwards until they ran out of space. Then they took over part of the garden at the back and enclosed it. And then they moved down the block to the corner of St James and Main Roads where they had 40 tables and 15 waiters. “On Saturday nights, people used to turn those 40 tables three times,” Franc said.

Aldo and Onorina also bought a row of cottages and built apartments on top of the new restaurant, which they rented to tenants. “They arrived here absolutely penniless, borrowed 90 pounds, set up that restaurant with the gondola, managed in a few years to buy all those cottages and build the block of flats and the restaurant; and within three years they had sold on the restaurant because Franc’s father became ill and couldn’t run it anymore,” said Carol.

By the late 1950s, two other Italians named Franco and Carlo had set up their restaurant down the road from Venezia, called Fracarlo. “They came to have something to eat at our place,” said Franc. “It was late in one afternoon and they asked for some omelettes. My dad started talking to them and they said, ‘We’re opening up there, we’re opening an upmarket restaurant.’ ”

Onorina got up to make the omelettes. “When she collected their plates afterwards, they said it was the worst omelette they ever ate. So Carlo got up and went to teach my mother how to make one.”

When Carol and Franc were at Fracarlo one night, Carlo said to Carol that he had taught Onorina how to cook. “She couldn’t make an omelette!” he told her. He also spent a few days teaching Onorina the finer points of Italian cooking: how to prepare and keep pasta for multiple orders so one wasn’t boiling each portion from scratch, for example.

“My mom didn’t know how to cook in bulk,” Franc said.

“She was just a housewife who cooked, and it’s different when you cook just for your family and when you cook for a large quantity of people,” Carol added.

“And a variety of plates,” said Franc. “The food was good. It wasn’t superb. It was good and it was cheap.”

“And it was different. But the ice cream was superb,” Carol said.

Carlo might have taught Onorina how to cook his way, but Onorina taught Carol how to cook hers. One dish she taught was her lasagne. The recipe went on for 20 pages. Carol has subsequently abbreviated it but it still makes a “very nice lasagne”. While Onorina’s other sister, Francesca (Cesca), taught Carol how to make minestrone. The vegetables needed to be cut into very small pieces and there should be lots of them because, as Cesca put it, “more put, better come.”

Cesca and her husband, Olivo Todesco, had followed the rest of the family to Cape Town in the fifties. Olivo worked in the restaurant and learned from Aldo how to make the ice cream. With a partner, Silvio Lazzari, he eventually bought Venezia from Aldo and Onorina.

According to Carol, Franco from Fracarlo had been the maître d at the Langham Hotel in Johannesburg, where she suspects Carlo was the chef. “Carlo was absolutely famous for making osso buco. Nobody knew about osso buco and it was his signature dish and he made it superbly. He had these big black pots and he came into the restaurant shaking these pots under everybody’s nose. He always wore a tuxedo.

“And then one night Franc and I were there for dinner and there was a couple sitting a table away from us who were obviously having some sort of domestic problem and she was crying, but she managed to order a sole. Carlo did wonderful grilled soles: big west coast soles. And he brought the sole and she took a mouthful and she was still crying and she said the sole wasn’t well cooked enough. So Franco took it back to the kitchen and he brought it back again, and she was crying more and she said no, this sole’s not right. So he said to her: ‘Signorina, please, if I take it back to the kitchen this time, Carlo will be crying!’ ”

In Sea Point, other Italian eateries began to open. There was Pizzeria Napoletana further down Main Road, opened by Luigi and Maria Barletta in 1957. In the opposite direction, Vesuvio opened on the corner of Main and Glengariff Roads. “I think it was my first grown-up date there (not with Franc) and I can still remember what I ate,” Carol said. “It was a steak with peppers. It was absolutely delicious.” Vesuvio then moved to the city centre and was renamed Capri.

Also in the city centre was La Perla on Waterkant Street, situated next to The Metro, one of four cinemas in the area. It was a coffee bar – which was also an entirely new concept in Cape Town – started by Cleto Saporetti, a former prisoner of war, and Emiliano Sandri, a former contract waiter on the South African Railways. Sandri later closed that outpost of La Perla and in 1969 reopened on the Sea Point beachfront. The Sea Point La Perla has endured as one of Cape Town’s classic restaurants – along with its career waiters and retro fixtures.

“It was an era when Italian things became very popular. A lot of Italian films came out. I think it started with Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday, and people became very fascinated by anything Italian. There was a lot of Italian music, like Volare and Al di là,” Carol recalled.

She also reckoned that because many South African troops were stationed in Italy during World War II, and fought their way through Italy as part of the allied forces, it started a trend towards everything Italian.

“It was one of these things that happens. Something becomes the in thing of that time. Certainly Italian food did. It translated well, it moved well, it travelled well. It worked for the times, and it has never stopped working.”

Prior to World War II, there were six to seven thousand Italians in South Africa – mostly in Johannesburg. Not even a thousand were in Cape Town, according to Maria Grazia Martinengo, who was born in Italy and moved with her family to Johannesburg in 1949 when she was six and couldn’t speak English. “We were considered second-class citizens,” she said.

Martinengo has worked for the Italian community as a researcher, interpreter and events organiser her entire adult life in Johannesburg and Cape Town, where she’s lived for more than 25 years. She’s often called on to give a talk she developed entitled A Brief History of the Italians in South Africa. In 2010, the Italian government awarded Maria an order of knighthood for her services to the Italian community in SA.

One slide in her talk is the first recorded photograph ever taken of an Italian in South Africa, from 1884. Since Italy had aligned with the fascists, Italian civilians in SA were interned during World War I, World War II, as well as the First and Second Boer Wars.

There were 100 000 prisoners of war in the Zonderwater camp near Pretoria after WWII – which was the largest (or second largest, depending on the source) allied detention camp in the world. It was set up in 1941 for Italian soldiers captured on the northern and eastern fronts of Africa. In 1947 the men were repatriated, except for 850 of them. In their early twenties and many from food-oriented backgrounds, they were permitted to stay and were given permanent residence.

By the early 1950s, about 20 000 more returned from Italy when commercial opportunities became available to them. “South Africa was growing at a rate of knots,” Martinengo said. By 1965, there were about 65 000 Italians in SA: 40 000 in Johannesburg and surrounding areas, and the rest all over the country, although not many in Cape Town.

“The difference between the immigrants then – why they came to South Africa – and why they’re coming now, is completely different but the same.”

In 1956, aged 22, Luigi Scaglia was one of approximately 100 young Italian men to garner a two-to-three-year contract with the South African Railways, along with Sandri and a future business partner, Luciano Bersella. The then minister of transport, Ben Schoeman, had Italian prisoners of war working for him and he “probably liked them”, said Scaglia.

Schoeman came up with the idea to add Italian stewards and chefs on the Blue Train between Pretoria and Cape Town, which remains one of the most luxurious train experiences in the world. So the government paid for their passage, put them up and gave them employment.

After their contracts ended, these men could do whatever they wanted. Many went to work in the hospitality industry and then set up their own food businesses, like Sandri from La Perla. Scaglia went to work in the Royal Hotel and the Milroy after which he opened Lerici in the residential and university suburb of Rondebosch and, later, Luigi’s, in the more commercial area of Woodstock. After a year’s break he took over Venezia, rebranding it San Marco.

Scaglia didn’t know when he arrived in Cape Town and took a room above Venezia in one of the flats the Stefanuttos rented out, that one day he would own their business. “It was the only Italian restaurant we can go and eat. Those days when we came to this country, I remember that the ordinary menu on most of the cafes and most of the restaurants was steak and egg, sausage and mash, and crayfish mayonnaise.

“There was the Alhambra, the Waldorf (for cake and tea), the Marine and the Mount Nelson. That’s all. I think people wanted something new. Although, South Africans, they weren’t travelling as they’re travelling now.

“When I sold the place in Woodstock, I told my wife we were going to look for a small place in town that I can open perhaps at 7 o’ clock in the morning till 5 o’ clock.” Instead, he wound up with a place where he had to work from eight in the morning till one in the morning. That place was San Marco, which from the end of 1979 until 2001 when he sold it, was one of the most popular, best-loved restaurants in the city.

When he bought Venezia, Scaglia decided to change the name as he wanted to change the image of the place. He also changed the interiors, making it a little bit smarter – smart “for those days”, he said. He bought a semi-industrial machine from Italy to make pasta. Menu favourites included the classic tomato and bolognaise sauces to ones with cream and mushrooms. He made ravioli filled with meat or ricotta and spinach. There was a lot of fresh fish and seafood, veal, steak.

He also served carpaccio. “Nobody had it in Cape Town. I copied the recipe from a place in Venice; I got the recipe by chance. We had the grilled calamari, which nobody used to make. I started it.”

In their retirement, Scaglia said he and his wife, Laura, didn’t go out to eat – even to Italian restaurants. She was a good cook and they preferred to stay home. “Italian restaurants should have, first of all, a person who is an Italian that knows how Italian food looks like and tastes like. They should use at least three Italian ingredients. Not everything taken from the country where you live. Certain items that can only be Italian: say, the parmesan cheese, where do you find? Tomatoes: nobody can beat Italian tomatoes. Things like that. You know if you don’t use that, what kind of Italian restaurant it is?”

As a postscript to this, San Marco closed a few years after Luigi Scaglia sold it to another local Italian family. And he died in 2016. Franco Stefanutto died in 2019 while he and Carol were in the process of finalising their emigration to Italy. Carol now lives in a small town on Lake Garda. Their son, Rob Stefanutto, continues to make the ice cream in Cape Town from his grandfather’s recipes.

You forgot to mention one of the pioneers of the Italian restaurant industry in Cape Town, Luciano Bersella. After completing his contract on the railways, he and Emiliano Sandre bought La Perla in town. They were very successful together, however they split up and Luciano opened the Lerici chain, Mamma Rosa and several other restaurants. Luigi worked for Luciano at Lerici in Woodstock. The other Lerici's were in Rondebosch and cental Cape Town in St. John's Place.

There is a photo of Luciano at La Perla in Sea Point now showing him at the original La Perla in town. He sadly passed away in 2004.

That was really the most fantastic history of sea point ! I remember Fracalo so well carrying a huge dish of his osso buca and of course who doesn’t remember San marco and the Venezia ! And then la Perla landed on the scene. Still as popular today - we used to go for toasted crayfish sandwiches in the 70’s. Dominique u have researched the subject so well👌👌what an enjoyable read